My first two posts on getting started and pivoting came from a product management perspective; to keep things lively, I’m writing this third case-study on how I utilized machine learning (ML) to create AI opponents for my game. But before I jump right in, I should briefly discuss why I chose to go down the ML route as well as explain the mechanics of Riposte!

Why ML?

The biggest reason why I went with ML instead of hand-crafting AI players was that I tried the latter and I could not make them fun. Very early on in development I made several iterations of AI opponents using finite state machines. I was unable to get them into an acceptable middle ground- they were obnoxiously good in terms of control and accuracy, while at the same time boringly simple at strategy and tactics. I estimated it would take me over a month of full-time effort to get one into working shape. So when I pivoted the game design away from a single-player/co-op campaign to a party-fighting-game I put AI opponents on the back burner.

Nearly a year later I decided on a whim to give AI players another try. Partly to give an otherwise fully multiplayer game some hint of single-player content. And partly because machine learning is just plain cool. It also helped that I had built the game in Unity and could use their ML-Agents toolkit.

How Riposte! Works

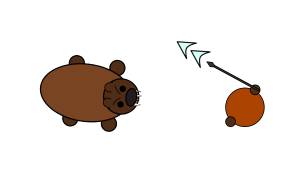

For context I should probably give a brief description of the control system in Riposte! It’s a controller based fighting game where the player moves the weapons instead of the characters. The weapons all fly around, and the characters follow and retreat automatically depending on the distance to their weapons.

The weapons are controlled via a single analog stick, which directly translates them and indirectly rotates them (the weapons will rotate toward the inputted analog stick degree). There are two available actions, set to buttons. One locks the rotation so that you can choose to only translate, the other performs a special ability unique to the weapon. For the initial AI opponents I trained them without the use of special abilities.

The goal of the match is to stab the other character and to not get stabbed yourself. The swords are segmented into multiple sections & colliders so that different types of collisions create different levels of knockback deflection and rotation. Hitting another player’s hand creates the largest amount of deflection and is a primary tactic.

The Goal

Although the core of the main game is a 2v2 fighting system, my goal for the AI agents was to create a practice 1v1 gauntlet mode, a la Bushido Blade’s 100 opponent ‘Slash Mode.’ So I didn’t want an extremely good AI opponent. I wanted several different profiles of differing degrees and styles, so that I could pit the player with a single life against back-to-back escalating enemies.

Setting up for ML-Agents

I won’t get into the details of the installation process, as the installation instructions already cover that fully, but it was relatively straightforward. Before I even thought about how to set up my own training environment, I imported and ran through several of their provided examples. I strongly recommend reading the docs and doing the same.

The first major hurdle was building a training environment in my game. As a silly party-game, Riposte! has a ton of superfluous fanfare that I didn’t want slowing down training: pauses in-between rounds, zooming & panning in on hits, dumb banter at the start of match, trumpets and confetti at the end, etc. Additionally, the matches all have an imposed structure: best of 3 rounds, with up to 3 points per round (depending on armor), and a match timer which I had to remove.

Once all that juiciness was gone and the match structure lightened so that it would instantly reset, I moved on to wiring up the agents.

Wiring a sword to be controlled by an AI Agent

For my use-case, it was super simple to give the AI brain control over the sword. I modified my existing sword control script to have an “isAIControlled” toggle, and if set, then to use a small array instead of control input.

Next I made my own Agent and made it pass its vectorAction array inside its AgentAction() method to the weapon control script.

public class AIGymSwordScript : Agent

{

… Other stuff…

public override void AgentAction(float[] vectorAction)

{

baseWeaponScript.SetAIInput(vectorAction[0], vectorAction[1], vectorAction[2]);

}

}

The AI brain only has 3 continuous outputs which correspond to the x- and y-axes of the joystick, and whether the rotation-lock button is held. These get clamped to -1 to 1 in the weapon script.

Getting information to the AI Agent

The next step is deciding what information I think the network needs to make decisions. In my case it needed to know about: its own position and rotation, the enemy weapon position and rotation, and the position of both characters. Although in theory the network can learn to infer other information about the weapons (e.g. the position of the hand, where the tip of the sword is, etc.) I decided to help it out by directly including some of those.

public override void CollectObservations()

{

AddVectorObs(this.transform.position / 10f);

AddVectorObs(tipTransform.position / 10f);

AddVectorObs(handTransform.position / 10f);

AddVectorObs(myCharacterObj.transform.position / 10f);

AddVectorObs(enemyCharacterObj.transform.position / 10f);

AddVectorObs(enemySwordObj.transform.position / 10f);

AddVectorObs(enemyTipTransform.position / 10f);

AddVectorObs(enemyHandTransform.position / 10f);

AddVectorObs(this.transform.rotation.eulerAngles.z / 360f);

AddVectorObs(enemySwordObj.transform.rotation.eulerAngles.z / 360f);

}

In the training environment I set those various transforms and gameobjects in the inspector. Later in using the AI agent dynamically in the real game they are set by the script managing the match.

Additional ML-Agent pieces

The final step is adding BehaviorParameters (with the action and observation vectors set appropriately), and the DecisionRequestor:

Rewards

Once the environment is working and the agent is capable of moving the sword it was time to define the reward criteria. For the agent to learn it needed feedback on whether it was succeeding or failing. As a general rule, you should start as simply as possibly and only add more complex rewards as you iterate if you need to encourage specific behavior it is otherwise not learning.

I used three types of rewards in training the sword AI agents: win/loss rewards when a character is hit; smaller rewards on weapon clashes dependent on the type (e.g. strong vs weak); and very small rewards per timestep to encourage movement or stalling (depending on what behavior I was going for).

In the first setup I only used the most basic win/loss rewards, through methods that get called by the match manager.

public virtual void DoHit(Tags.CharacterTag characterTag)

{

//Debug.Log("done hit");

SetReward(1.0f);

Done();

}

public virtual void GotHit()

{

//Debug.Log("done got hit");

SetReward(-1.0f);

Done();

}

Later I moved on to other types of rewards which attempt to encourage good weapon clashes. I had to keep these very small otherwise they would overpower the main objective. In one case I accidentally trained two swords to trade off attacking each other’s hands, completely ignoring hitting the characters, to maximize their reward per match.

public virtual void DoClash(Tags.WeaponTag weaponHitBoxType, Tags.WeaponTag enemyHitBoxType)

{

switch (enemyHitBoxType)

{

case Tags.WeaponTag.Gauntlet:

SetReward(0.1f);

break;

case Tags.WeaponTag.Hilt:

SetReward(0.1f);

break;

case Tags.WeaponTag.Weak:

SetReward(0.1f);

break;

}

switch (weaponHitBoxType)

{

case Tags.WeaponTag.Gauntlet:

SetReward(-0.1f);

break;

case Tags.WeaponTag.Hilt:

SetReward(-0.1f);

break;

case Tags.WeaponTag.Strong:

SetReward(0.1f);

break;

case Tags.WeaponTag.Guard:

SetReward(0.1f);

break;

}

}

Another time I set the positive and negative reward too high for a hand hit and one sword learned to bide its time and only attack the hand while the other tried to hide in the corner.

Hyperparameters

Hyperparameters, hyperparameters, hyperparameters! These are simultaneously the most important and most confusing part to new users. There are quite a few of them and they interact to determine how learning occurs.

Repeating my earlier sentiment, start small. I began with a network size of 128 nodes x 2 layers, and iteratively increased it until the swords moved smoothly and learned actual tactics. I ended up testing networks up to 1028 x 4, but ultimately settled on 512 x 3.

Stability

In the description of a lot of the hyperparameters it says that they affect and often trade off between stability and rate of learning. Personally I am impatient and greedy so I try to ratchet up the learning rate, usually to the detriment of stability. What this means in practice is that the agent can end up locking in on some weird, local optimum and never recover.

Training within Unity

While it is much faster and more efficient to train with a standalone executable, you should first confirm that everything works and that the agent is actually learning. To do this you can run the ml-agents command without an env= and it will wait to connect to the Unity editor, where you can then hit play. I still make this mistake when I am in a hurry, and it has wasted more than a little time, because it is difficult to know early on if something isn’t working while training externally.

mlagents-learn ...config\trainer_config.yaml --run-id=SwordVSShield021 --train

Adding Initial Randomness

As a fighting game it was important that each match start out from the same initial, symmetric conditions. However, for training purposes I added small random positional and rotational offsets at reset in order to get the swords exposure to a greater variety of situations and have more robust training.

Multiple Matches within a Training Gym

Once you’ve confirmed that everything is working as intended with a single match you can add multiple matches to speed up training. This took a little extra re-jiggering to get my game to function, as originally the setup made some assumptions on the default position of characters and swords.

Training with Multiple Standalone Environments

Next up we build the gym scene into an exe and then we can train at maximum efficiency!

mlagents-learn ` ...\config\trainer_config.yaml ` --env=...\Builds\training\SwordVSShield2\Riposte.exe ` --num-envs=8 ` --run-id=SwordVSShield022 ` --train ` --no-graphics

Keep Records

As you train different sets of rewards, observations, actions, and hyperparameters it can be difficult to determine which is working well. I recommend recording and commenting on the outcome, either in a txt file, spreadsheet or elsewhere (I just put notes in the config yaml).

## 021 # Only +/- 1 on hit. # 8 environments, 16 matches per env ## Attacks okay, makes very little effort for defense. SwordDumbAttackerBrain: trainer: ppo max_steps: 1.0e8 learning_rate_schedule: linear batch_size: 8192 buffer_size: 131072 num_layers: 3 hidden_units: 512 time_horizon: 2000 summary_freq: 5000 normalize: true beta: 5.0e-3 epsilon: 0.2 lambd: 0.95 num_epoch: 4 reward_signals: extrinsic: strength: 1.0 gamma: 0.99

Training using Self-Play

Unlike the above gif which is training a sword against a shield, ML-Agents has an implementation of a really cool self-play algorithm, where the agents are scored with an ELO and play against ever improving versions of themselves. It does take significantly longer in terms of steps than the ad-hoc adversarial training I was previously doing, but resulted in the best general AI opponents I was able to make.

The setup is largely the same. The biggest change was going back to the simplest possible rewards and remembering to set the team_id for the swords correctly. After iterating across multiple self-play setups, I settled on training with +/- 1 reward for winning/losing and small additional rewards/penalties for hand hits.

## 180 # 16 matches, 8 env # +/- 0.25 on hand hits # -0.001 per tick if center out of band, -0.005 per tick if tip off screen # removed decreasing hand hit reward/penalty. ## Not too bad! Could be smarter. SwordGeneralBrain: trainer: ppo max_steps: 2.0e8 learning_rate_schedule: constant learning_rate: 8e-4 batch_size: 8192 buffer_size: 131072 num_layers: 3 hidden_units: 512 time_horizon: 2000 summary_freq: 5000 normalize: true beta: 5.0e-3 epsilon: 0.2 lambd: 0.95 num_epoch: 4 self_play: window: 15 play_against_current_self_ratio: 0.45 save_steps: 60000 swap_steps: 30000 reward_signals: extrinsic: strength: 1.0 gamma: 0.99

Overall Post-Mortem

Moderately successful! It took more work than expected to make my game fit for ML-agents training. Not a stupendous amount, but it wasn’t trivial. If I had planned on doing this from the start and had less coupling it would have been smoother.

Self-play produced the best overall agents- I can still win 9/10 times if I’m trying, but they put up a good fight sometimes. Even within a self-play paradigm I had to give additional rewards on top of the +/-1 for winning in order to better encourage certain tactics I knew to be optimal.

The top performing agent along with a couple dumber but tactically different agents were enough to make a satisfactory gauntlet mode experience. The gauntlet format combined with some extra help for the bots (they get armor as the enemies progress, etc.) really brings it together.

TL;DR Take-aways

- Read the docs and do the examples!

- Test if rewards are functioning and agents can actually act by training within Unity first.

- Slow and steady is better, start with a smaller learning rate and num_epochs, etc.

- Start with simpler rewards before adding complexity.

- Start with a smaller network first, then add more nodes & layers if necessary.

- When training multiple matches & environments you need to increase your buffer and batch size to remain stable.

- Randomizing initial conditions helps agents learn more robustly.

- Keep any additional non-primary goal rewards small.

- Be careful with negative rewards, they can easily lead to only learning to avoid the penalty.

- Self-play works very well, but can take longer.

- Record notes on the setup: rewards, hyperparameters, etc. to help you iterate.